From Italy to the global scenario

A journey through architecture and design

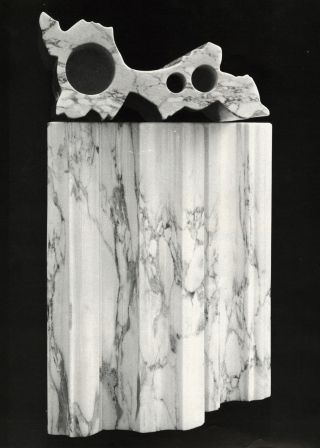

Angelo Mangiarotti, Variazioni vase for Officina, 1966.

View and details of a prototype in Calacatta Oro marble

In the mid-1970s a new debate around the renovation of stone production in Italy began: crucial was the cultural and manufactural experience of the Officina workshop, started in Pietrasanta but developed through several international contacts, and also thanks to the personal experiences of designer and critics such as Pier Carlo Santini, whose purpose was to renovate and requalify objects and furnishing made of stone. In this context Angelo Mangiarotti’s contribution was also essential, in particular through his machine-carved stone vases called Variazioni.

Variazioni vases

This collection, created with the most significant marbles from Apulia as the Calacatta Oro, included eight configurations with one, two or three holes; the milling of the blocks produced dramatically different outlines, tense and highly chopped, with no need of changing the production process.

Officina promoted experimentation in the field of the industrial production, anticipating a new golden age of the stone projecting culture that started shortly afterwards and skyrocketing, from the 1970s till this day, Italian stones into the global scenario of architecture and product design.

Alvar Aalto with Jean Jacques Barüel, Nordjylands Kunst Museum in Aalborg, 1972.

View of the front, marble details in the interior and a slab of Carrara marble

Aalborg Art Museum

In those years we could see a widespread circulation of materials, designers and stylistic expressions, to Italy from abroad and vice versa, here perfectly summarized by the Art Museum in Aalborg, Denmark. With its ziggurat-like structure completely covered with Carrara marble (also used for the refined details of the interiors), the building shows how a master of contemporary design such as Alvar Aalto loved the traditional materials he could appreciate in historical Italian cities. The Carrara marble in particular was again used in other works in the more mature phase of the architect’s career, as in the Cultural Centre in Wolfsburg and the Finland-Talo in Helsinki.

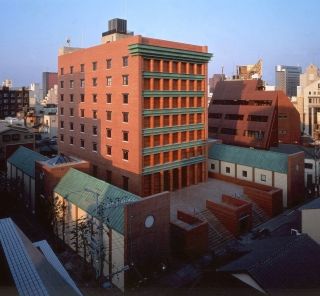

Aldo Rossi, Palace Hotel in Fukuoka, 1987-1989.

General views and detail of a slab in Red Persian Travertine

Contemporary stone culture follows not only the transfers of materials but also the circulation of ideas from its best representatives: it’s the case of Aldo Rossi, who at the end of the 1980s mixes his peculiar projecting style with the dense and vital texture of Japanese cities, designing a stone palace-shaped hotel in Fukuoka. The entire building is summarized in a façade with half-columns in Red Persian Travertine and in huge string courses made of green metal. This type of stone, employed in other parts of the hotel as the main staircase or the access arch, is the medium through which a bridge between two cultures is built: “The Fukuoka palace is furrowed by an acid, mineral and vegetal green as in stones abandoned in parks and covered by a kind of sick nature”, Aldo Rossi said, “and this green crosses the veined red-orange stone coming from the most ancient empire, Persia, that is gateway to the East and mother to the West” (A. Rossi, quote in V. Pavan, Il linguaggio della pietra, Venezia, 1991, p. 99).

Grafton Architects, Addendum to Luigi Bocconi University in Milan, 2004-2008.

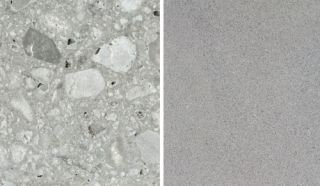

Volumes covered in Ceppo di Gré and a view of the auditorium covered in Pietra Serena

Back to Italy, another mix between the highest international projecting culture and the tradition of local stones is the Bocconi University in Milan, designed by the Dublin-based Grafton Architects. The monolith aspect of this architecture is sternly but also vividly expressed by the total covering in Ceppo di Gré, a stone quarried on the shores of Lake Iseo, historically used in Lombardy as freestone with no interruption from the Latin age to the 20th century. The same stone is used in the interiors as well next to other Italian materials as the Bianco Lasa marble, the Carrara marble and Pietra Serena, all employed in floors and walls.

Ceppo di Gré (left) and Pietra Serena (right) slabs, details

by Davide Turrini